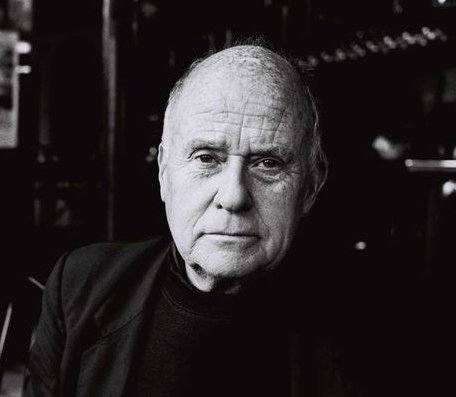

A new tribute to Jean Rouch

Paris, 20 September 2017

A prolific man, Jean Rouch directed more than 180 films. He was also well versed in poetry and ethnology. Today, several institutions are celebrating the centenary of his birth.

In 1957, Jean Rouch released Moi, un Noir, a film shot in pre-independence Cote d’Ivoire, which followed the daily lives of three Nigerian migrants. When the film came out, Jean-Luc Godard wrote three articles about the director and hailed him as the “free man” that he was: “the title on Jean Rouch’s calling card says it all: researcher for the Musée de l’Homme, the Museum of Man. Could a finer definition exist for the filmmaker?” Several years later, in 1960, Godard even contemplated titling his first feature film Moi, un Blanc — which posterity would come to know as À bout de souffle.

Going back to Rouch, this filmmaker discovered Niger at the age of twenty-five, and fervently explored its capital, Niamey, before pushing the doors of Africa open wider. As a connoisseur of the continent, this “free man” produced work that stands out for its handling of Africa, taking an approach that was not only ethnographic, but also aesthetic, political and poetic.

Back to the Source of Inspiration, NigerJean Rouch was born in 1917 in Paris. His explorer father transmitted to him a taste for travel very early on. He had a happy childhood in Rochefort until World War II broke out. In 1942, as a bridge and road engineer, he was posted to Niger by France’s Vichy regime. In Niger, as his last wife Jocelyne Rouch recounts, “he attended a body purification ritual for people struck by lightning on a worksite. Deeply moved and touched, he immediately wanted to understand the ceremony that he had witnessed, as it opened up the gates of wonder to him. His vocation as an ethnologist began at this point. His friend Damouré Zika, who he met at the riverbank, would become his guide towards the discovery of the Songhai culture.” Jean Rouch returned to Paris and studied under Marcel Griaule, who would become his spiritual father, before returning to Niger to film Songhai rituals, with a camera hitched over his shoulder — a technique that was excluded from filmmaking practices until then. In 1947, with two friends, he became the first man to descend the Niger River in a canoe, from the river’s source to its mouth — a 4200-kilometre trek. Profoundly affected by these first encounters, he would go on to divide his life between Niger, France and the rest of the world.

Showing a Changing AfricaIn 1949, his ethnographic research film, Initiation à la danse des possédés, was presented at the Festival du Film Maudit, an early event for art films organised by Jean Cocteau and Henri Langlois. The film was shown in cinemas as a prelude to Roberto Rossellini’s Stromboli. While Jean Rouch filmed ethnological investigations into Africa’s religious rituals, he also developed a passion for Modernity, namely influenced by Michel Leiris and his L’Ethnographe devant le colonialisme (1950) dealing with Africa, a text that was more or less ignored by ethnologists until then. He rapidly turned his interest to the urban world, industrialisation, labour, the working classes who occupied shanties and lived in difficult conditions — themes that would crop up in his films.

In 1953, with the support of Marcel Griaule, André Leroi-Gourhan, and Claude Lévi-Strauss, Jean Rouch created the Comité du Film Ethnographique as part of the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. The project was in line with the initiatives undertaken by UNESCO to raise recognition of the ethnographic documentary-film genre and to develop an inventory of this budding type of cinema. The Musée de l’Homme became the first museum in France, if not the world, to get equipped with a cinema. “The Musée de l’Homme is my home,” Jean Rouch would claim, and he showed, mixed and screened his films there. Later, in 1982, he also set up the Festival du Film Jean Rouch whose next edition, in November 2017, will be on the theme of happiness.

Following the creation of the Comité du Film Ethnographique, a series of shootings followed, including that of Jaguar, made between 1954 and 1967, a road movie about three Nigerians on their way to the Gold Coast, present-day Ghana, a former British colony. There was also Les Maîtres fous (1957), on the trance-like movement of Haukas, a poor community in Accra. In the same year, Jean Rouch shot Baby Ghana, a film on the country’s independence, an incredible portrayal of the lives of Nigerian migrants, with underlying themes of syncretic exchange, modernity and interculturality.

Then came Moi un Noir (1957), and later, during a sojourn in France, in 1960, Chronique d’un été, co-directed by Edgar Morin, a poignant depiction of France at the start of the Trente Glorieuses period. Between 1967 and 1973, Jean Rouch filmed, with ethnologist Germaine Dieterlen, Sigui ceremonies in Dogon that only take place once every sixty years. Throughout his career, Jean Rouch remained attached to the use of mobile autonomous cameras and collective work that left plenty of room for improvisation. In this respect, he was a precursor of today’s current practices.

Legacy of His WorkUntil he died, in 2004, as the result of a road accident in Niger, the French ethnologist continued his cinematographic research. Jean Rouch is buried in Niamey, and the country paid homage to him via a national funeral service. But he has been accused of not standing up strongly enough against colonisation, and at the time of Niger’s liberation, he met with the hostility of the country’s filmmakers, as well as others from France. Even though, as anthropologist Andréa Paganini, director of the association ”Centenaire de Jean Rouch”, points out, South African apartheid made Rouch “sick”, he was a discreet man throughout his life who avoided making waves.

Yet the ethnologist’s legacy transcends such debates. As Andréa Paganini also recalls, “Jean Rouch was a man of networks. In 1979 in France, he took over the Cinéma du Réel, he set up the Varan workshops in 1981, and it’s partly thanks to him that Nigerian cinema is as important as Senegalese cinema.” Jean Rouch also taught at Chaillot, Nanterre and the Cinémathèque, but his teaching style was free, “à la Langlois”, sidestepping the possibility of claims that he trained pupils or created a school. At the same time, many young filmmakers proclaim that they are his heirs. This is the case of Michel K. Zongo (born in 1974 in Burkina Faso), director of L’Espoir voyage in 2012.

While Rouch’s cinematographic works are modern and have infused contemporary creation, they remain little known, and some of his research, namely that dealing with possession rituals, has not been followed up. Should this be seen as a consequence of the fact that the bulk of his filmed work, conserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF) and the archives of the Fondation Jean Rouch, is not shown to the public?

Homages and Celebrations The centenary of his birth will nonetheless bring some of his films to big screens. The BnF is thus presenting one of Jean Rouch’s very first films: Bangawi (1947), rediscovered in 2009 by the CNC, which began gathering the ethnologist’s films in the 2000s and systematically built up an archive consisting of nearly 5000 of his film canisters. Bangawi captures a hippopotamus hunt by harpoon on Niger’s great river. More generally, “Jean Rouch, l’homme-cinéma” will be an opportunity, from 26 September onwards, to discover 200 large-format images by Jean Rouch and many restored extracts of his films. The exhibition covers fifteen themes ranging from the legacy of surrealism to the possession ritual dances that obsessed him. Light and comical, Rouch’s films are infused with his many friendships and point out the contrasting viewpoints of the European and his African accomplices — namely Damouré Zika, Lam Ibrahim Dia, and Tallou Mouzourane.

At the Musée de l’Homme, the exhibition “Dialogue photographique: Jean Rouch & Catherine de Clippel” will show rare photographs by these two artists separated by one generation. Designed by Jean-Paul Colleyn and Laurent Pellé, director of the Festival International Jean Rouch, this exhibition will present 120 to 140 photos on 4 to 5 major themes, from possession to mourning, mainly among the Dogon people. Also taking place at the Musée d’ l’Homme, the Festival Jean Rouch will similarly be celebrating the filmmaker’s centenary with a dense programme including screenings of restored films from the CNC’s archives. The films in question, both fictions and documentaries, are not well known, among them Dionysos (1984) and Enigma (1986), filmed in Turin. The film Bangawi will also be included in this lot.

This set of events will be accompanied by a host of debates, talks, screenings, that will delight aficionados while enabling neophytes to discover the “ethnofiction” so dear to Jean Rouch.

Memo

“Jean Rouch, l’Homme-cinéma” From 26 September to 27 November 2017. Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Quai François Mauriac. Paris 75006. www.bnf.fr

“Regards Inversés” Cycle of screenings and meetings. Saturday 7 and Sunday 8 October 2017. Musée du Quai Branly. 37 quai Branly. Paris 75007. www.quaibranly.fr

“Dialogue photographique: Jean Rouch & Catherine de Clippel” From 25 October 2017 to 7 January 2018. Musée de l’Homme. 17 place du Trocadéro. Paris 75116. www.museedelhomme.fr

Festival International Jean Rouch From 8 November to 3 December 2017. Musée de l’Homme. 17 place du Trocadéro. Paris 75116. www.museedelhomme.fr