Tribal Art Market 2017

Paris, 17 September 2018

Handovers to the next generation, a rise in the number of objects on sale, the creation of events on the market, a change in the way players behave... 2017 was a good year for arts hailing from outside Europe, but it looks like it might have been a transition period.

For around twenty years now, both auction figures and observations made by dealers and experts have attested to a healthy growing tribal-art market, which tends to be stable in its practices. In auction rooms, 2017 confirmed these sound results with a return to growth after two fairly flat years. Achieving a turnover of a little over €80 million, this is the second-best year in the history of the market (which includes classical African, Oceanian, pre-Colombian and North American arts) following an exuberant2014. This year, Sotheby’s sold the Frum and Myron Kunin collections, which together accounted for sales totalling €45.5 million. A hefty enough figure to tip the scales... “The market is doing very well,” enthuses Laurent Dodier, a French dealer and valuer from Normandy. “Thankfully, because we’ve been working for this for many years!”

The “big replacement”?

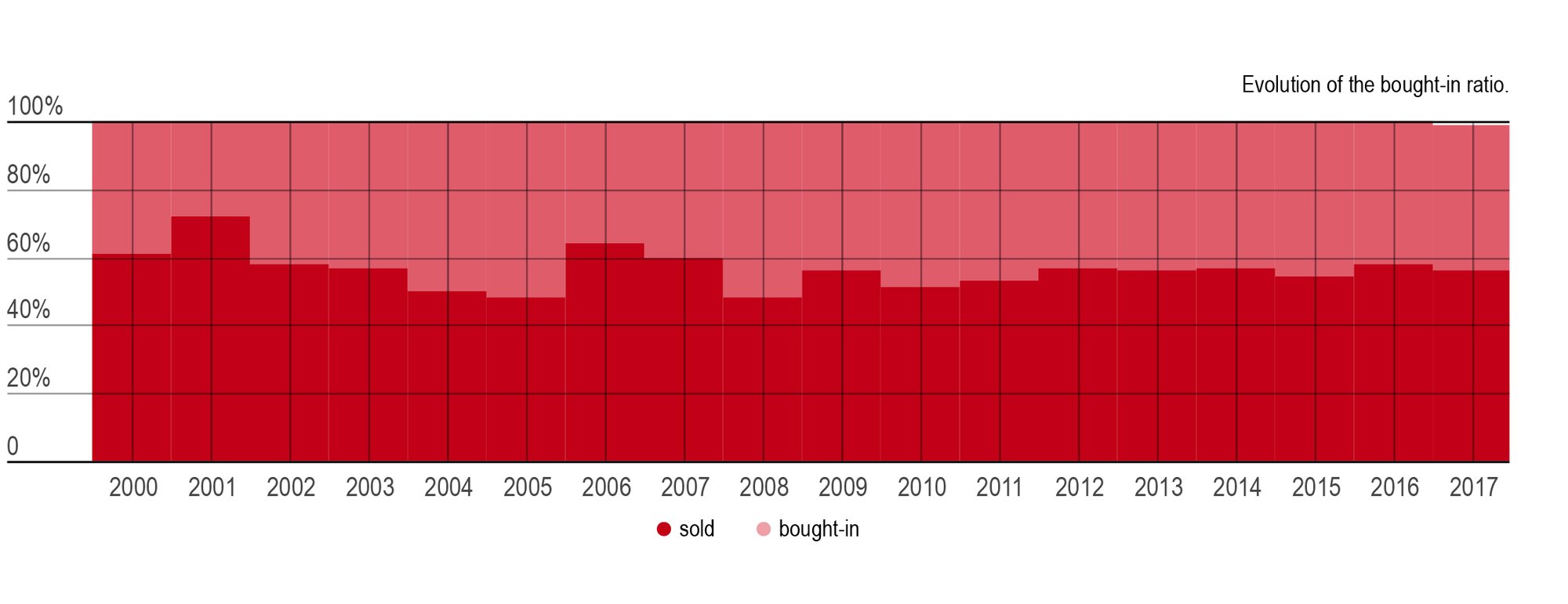

Yet behind this semblance of stability, the last few years have given out a few contradictory signals. For example, between 2012 and 2017, a huge boost in the number of pieces placed on sale was not necessarily matched by a rise in turnover. In 2017, the number of pieces going on auction went up to an astonishingly unprecedented 9,500. On average, around 3,100 objects were placed on sale every year from 2000 to 2005, compared with nearly 5,800 in 2014, 7,050 in 2015, and over 8,300 in 2016. The unsold rate remains high, at 45%. However, its stability in the last ten years seems to indicate a natural rate for this market. Meanwhile, the average price of objects sold has gone back up: in 2017, the figure was slightly over €14,700 – compared with €7,800 in 2016, about €10,000 in 2015, and nearly €17,200 in 2006 (a spike that can easily be explained by several million-euro auctions that year).

“We’re reaching a tipping point,” notes Laurent Dodier. “All collections that were built up from the 1950s-60s onwards are reaching their endpoints. New access is opening up to estates left by these collectors, aged between 75 and 95 years. As a result, a huge number of objects are arriving on the market. Today, supply is higher than demand.” This partially explains the increase in the number of objects on the market. “We’re clearly seeing a shift in generation. Some dealers and collectors are disappearing and new ones are arriving. We’re going through a bit of uncertainty... even if I have no doubt that things will pan out.”

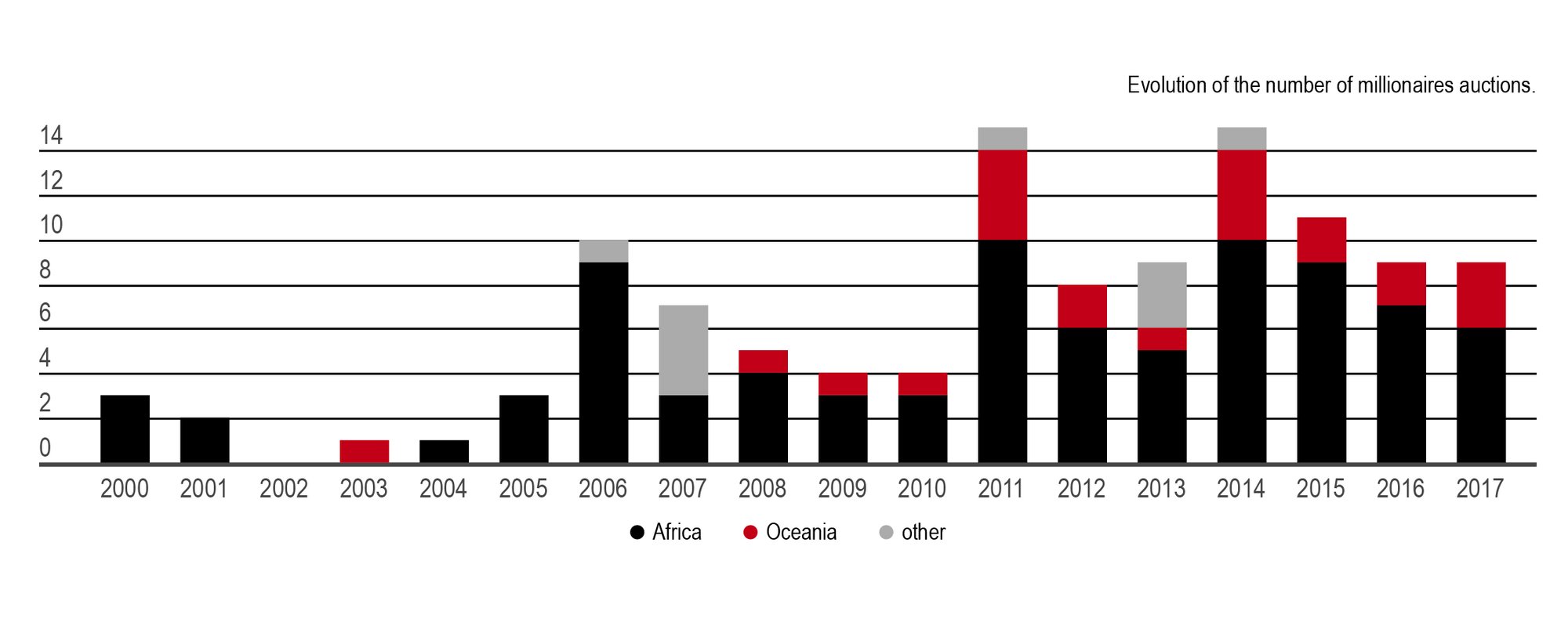

Records, records, records

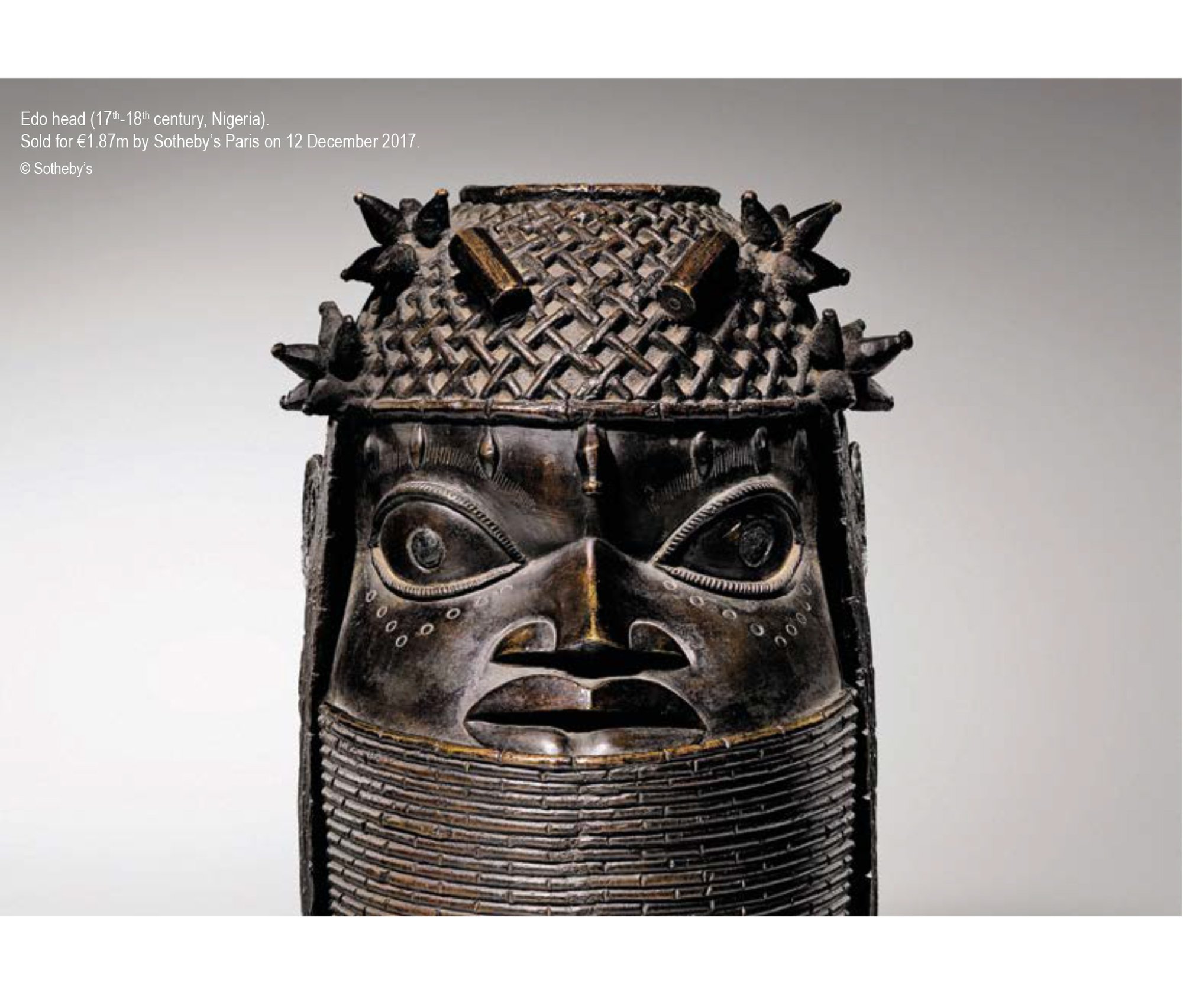

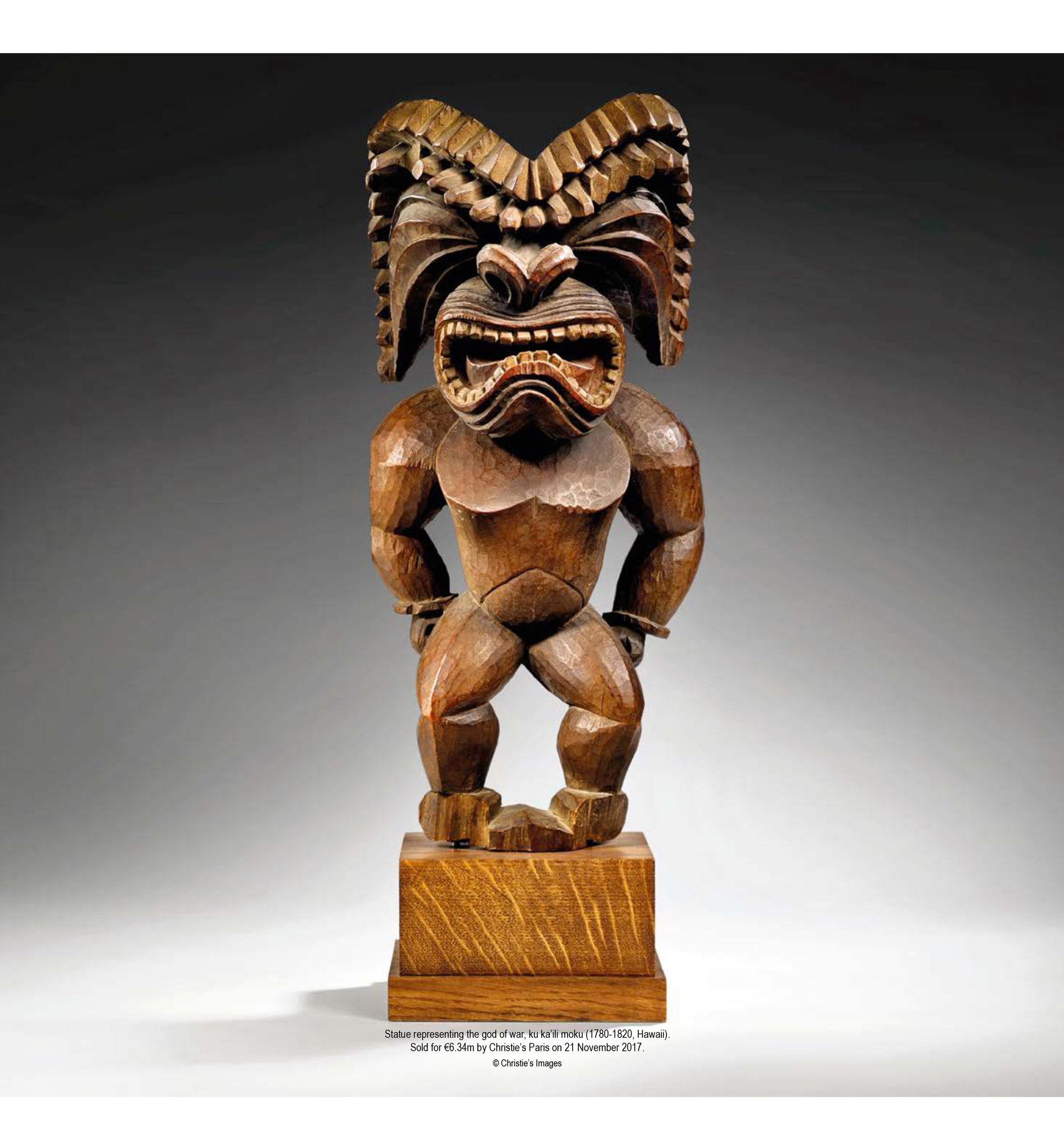

The other undeniable phenomenon in the last ten or so years is the emergence of an upper-end market, observable from the number of auctions raising millions: an average of 11 per year since 2011, compared with under four between 2000 and 2010. “We’ve seen an internationalisation and diversification of our collectors in the last ten years or so”, comments Théodor Fröhlich. “The market is also doing increasingly well for high-end pieces. People are really looking for quality. All this is positive.” Unsurprisingly, 2017 reaped its share of records. On 21 November 2017, during the sale of the Vérité collection – the second of the type after a historic sale in 2006 coinciding with the opening of the Musée du Quai Branly – Christie’s sold a Hawaiian Kona-style statue, produced between 1780 and 1820, representing the god of war Ku-ka’ili-moku for €6.34 million, and a Uli Uli ancestor statue from New Ireland for €2.97 million after it was given an estimate of between €200,000 and €300,000. Singlehandedly, this one sale raked in €16.7 million. Sotheby’s has nothing to complain about either, after selling a pair of rapa from Easter Island for €3.87 million, and also an Edo head from the Benin Kingdom (Nigeria, 17th- 18th century) for €1.87 million.

According to Canadian dealer Jacques Germain, “this spike in prices is largely due to the fact that most ’major objects’ have been identified, listed, and above all coveted by members of the ’tribal’ community. For this reason, at auction sales, their high quality and provenance make them trophies that are increasingly prized by connoisseurs.”

The Veblen effect

Auction houses, especially the Christie’s-Sotheby’s duopoly, are pursuing this upper-end strategy of accumulating “trophies”. Between them, in 2017, the pair represented a sales volume of €58 million, in other words 70% of the auction market. And this with while taking care of only 7% of lots placed on auction. No surprise that the twenty biggest sales of the year were organised at one or other of them. And if we remove these two giants from the picture, then we’re talking about a twenty-million or so euro market and the average price per object sold falls to €4,370. Among these other houses in the shadows, the ones that do the best are primarily French. Binoche et Giquello made sales tallying €5.5 million (with an average price per object of €24,220 and an unsold rate of 36%) while Millon produced €2.4 million (€7,212 and 42%). Bonhams, however,hadamediocreyear,withasalesvolume of €2.7 million and an unsold rate of 44%.

The upper-market strategy of Christie’s and Sotheby’s is quite straightforward: securing top pieces backed by impeccable pedigrees makes the prospecting and marketing stages all the easier. The two houses have two options for pulling off this strategy: focusing on prestigious collections and sets, or else scouting the worlds of modern and contemporary buyers to seduce collectors unfazed by six- or seven-figure price tags. In 2017, Christie’s sold the Vérité collection (€16.7million) and the Laprugne collection (€5.6 million) in Paris while Sotheby’s looked after Edwin & Cherie Silver’s collection (€7.13 million) in New York. Otherwise, the two houses have organised sales in New York to coincide with their major modern- and contemporary-art sales in June. In this way, Sotheby’s presented “Art of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas” – a selection that was “curated” according to the new fashion – which amassed $6.2 million (including a Chokwe female figure that once belonged to Jacques Kerchache) whereas Christie’s offered a tight selection of just twelve pieces that nonetheless raised a turnover of $3.9million. Note that Christie’s seems to refocusing its activity on Paris; the above-mentioned sale was the only one to be staged in New York in 2017 while the French capital concentrated 88% of its turnover. Over at Sotheby’s, things are more balanced (57% in Paris, 43% in New York). In short, for several years now, both houses have decided to sell fewer objects but at higher price levels.

“Christie’s and Sotheby’s – and a few others – have remarkable infrastructures. I’m not criticising the objects, which are marvellous,” confides Laurent Dodier. “But perhaps that’s not the case of their prices. These auction houses have a pool of collectors familiar with modern-art prices, and such prices are excessive for our market.” The dealer goes on to mention the example of an auction-house employee who had difficulty attracting collectors for an object priced at about €10,000 but no problems for an object with an estimated value of €100,000. Here we behold the Veblen effect – the phenomenon whereby demand for a good will swell up in step with its price. This is usually explained by psychological factors related to social signals associated with the purchase of goods at high prices or an effect on how quality is perceived.

Another phenomenon has entered the scene – and it’s one that auction houses know how to take advantage of: the jacking-up of the value of goods. Objects have an intrinsic value based on characteristics universally appreciated by the milieu: authenticity, age, the quality of execution, the condition, cultural usage... But they also hold an extrinsic value, an exchange value – one that is increasingly prominent in the current context of handover from one generation to the next. In other words, the value can be swollen by the fact that an object has passed through this or that collection during its successive sales, with prestige playing a non-negligible role. Finally, and this of course is not a phenomenon exclusive to arts from outside Europe, the soar in prices is also partially triggered by the history of the tribal-art market. While the quality of a kachina that once belonged to André Breton, Yves Berger or Charles & Ray Eames, remains unchanged, the same does not apply for its value in our symbolic system, hence its price. No new phenomenon as the history of the tribal- art market is already marked by prestigious sales, from Paul Guillaume to Helena Rubinstein, it is nonetheless beginning to be the norm.

Auction houses and dealers

So do these inflated prices represent the market’s reality? Or are they an epiphenomenon? The tree that hides the forest perhaps? Or shouldn’t they be seen as a reflection, through market value, of the recognised cultural importance of these objects in our system? “Why should African masterpieces sell for10 to100times less than some other paintings by modern-art pioneers who recognised the exceptional mastery of these African statues that inspired them?” asks Jacques Germain.

“Masterpieces in African art are rare,” argues Laurent Dodier. “The prices are appropriate for the works. But they’re bad press as far as collectors go. Many think that these are common prices, and it sends them running!” Julien Flak, whose gallery has been on the Rue des Beaux-Arts for twenty years, takes a similar view. “Records are an epiphenomenon. But they’re visible, they get a lot of publicity, they’re spectacular. There’s a reality outside of this, a market on which pieces can be found for a few thousand euros. It’s important that we don’t give in to these alarm signals and that we attract new people.” For Pierre Moos, the situation is clear: “In terms of dealers, there’s a drop in activity worldwide, due to competition from the major auction houses that scoop off the top of the market, but also, and above all, from Internet. Many of our clients are people who travel all the time. So for them, it’s easier to choose pieces from online auctions rather than going to real galleries.”

From flea markets to iPads: new practices

And it’s true that new times bring new practices. Many dealers mention, while not exactly complaining about, “enlightened art lovers”. No longer do people stroll around streets but over web pages; people are moving more quickly, visiting fewer museums, reading fewer catalogues and essays even if there’s a real upsurge of them... “When I started 40 years ago, we knew of around 30 ethnic groups in Nigeria, today, 350,” recalls Laurent Dodier. “We know more about objects. About their meanings and qualities. And then, we have a new category of wealthier collectors, who possibly haven’t had the time to get training. Perhaps collections are being built more (and even too) quickly?”

Meanwhile, Julien Flak points out the market’s tendency towards event creation. “20 years ago, we had antique-hunter clients. People came to the gallery because this was part of their habits; they came to see what we’d picked up. Today, there aren’t fewer people in galleries, but visitors wait for the right opportunity to come. And when they do, they can make snap decisions.” The dealer has thus chosen to hold flash sales. On the morning of 7June2018, for example, he presented a collection of kachinas in his gallery; in the evening, the exhibition closed. “I’ve never had as many sales or seen so many people in the space of 24hours!” In barely 6hours, three-quarters of the dolls had sold. “This isn’t a model that can be duplicated infinitely,” Julien Flak acknowledges, “but in certain conditions, it works.”

The development of social networks, Instagram sales... all these techniques are also multiplying, but the primitive-arts market still remains conditioned by its relatively modest size. From a more global perspective, it’s true that it only represents a tiny proportion of the 50 to 70 billion dollars tossed about by the art market depending on which reports or years referred to. “There are some trends, such as securitisation, which just won’t work for us for the simple reason that the market’s too narrow,” observes Laurent Dodier. “Sales platforms and sales via Internet are developing, but things are still vague. Legally, we need to put some order into all this.”

Africa and Oceania

In any case, Africa remains the leading continent when it comes to non-European arts. Oceania, too, is winning the favour of collectors, with prices rising quickly. In auction rooms, the market for African pieces totalled €38.8 million in 2017, as opposed to€27million for Oceania. Over time, the gap between the two is diminishing. “Collections are opening up more towards Oceania and America,” observes Julien Flak, “even they were uniformly turned towards Africa not so long ago.”

Indeed, Africa offers an abundance of pieces. The continent’s production dating back hundreds of years, wealthy both in terms of numbers and imagination, backs its dominance – at least in Europe, especially France and Belgium. Oceania’s market is smaller: rare supply, coupled with increasing demand, has led to the high prices that we’ve seen in recent years, with the biggest records set by Oceanic pieces. A trend also reflected by statistics: over 4,770 pieces originating from Africa were placed on sale in 2017, compared to 2,115 from Oceania – with both recording unsold rates of around 50%. The average price of an African piece is €15,500, as opposed to$25,600 for an Oceanic one. Since 2006, the median prices of pieces have basically followed the same direction: Oceanic art sells for more than African art. As far as Africa is concerned, the sought-after ethnic groups are still the same: the Fang and the Dogon. At auctions, Fang pieces sold for an average of€147,000 per piece in2017, a Dogon one for €45,800. Other regions are making headway on the market, namely America. Pre-Colombian pieces are a sound niche market, with a climbing turnover and fairly high average price of €14,500, and an unsold rate of only 36%.

In short, for many dealers, the modest size of the tribal-art market protects it from financial preying, and ensures its growth, which is tending towards steadiness despite the current shakeup. “When you sell a piece and the person wants to resell it three to four years later, it’s complicated,” declares Laurent Dodier. “Between the VAT, tax and expenses, there’s nothing left. But in the long term, collectors – and dealers – come out winners.”

Clément Thibault